Behind the words

“Behind this sad spectacle of words, unspeakably trembles the hope that you read me, that I didn’t die completely from your memory” – Julio Cortázar

“Behind this sad spectacle of words, unspeakably trembles the hope that you read me, that I didn’t die completely from your memory” – Julio Cortázar

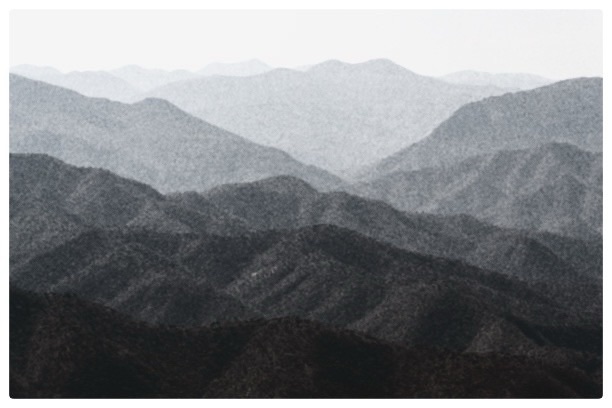

Y fue antes del principio,

cuando aún el sol no sabía su camino,

que la Madre se alzó de entre la niebla.

Alta y callada, coronada de nieve,

cubrió la tierra con su manto de pinos.

De su seno brotaron los ríos,

y el canto del agua fue su primer rezo.

Las bestias bebieron de sus lágrimas,

y los hombres hallaron en sus laderas la palabra “hogar”.

Al caer la tarde,

su rostro se tiñe de rojo y de oro,

y los cielos se incendian con su belleza.

Así muestra su rostro a los mortales,

recordándoles que la hermosura también quema.

Ella amó a sus hijos.

Los alimentó con frutos, los cubrió con sombra,

los dejó dormir bajo su aliento fresco.

Pero ellos abrieron su carne buscando tesoros,

y le arrancaron las entrañas sin mirar al cielo.

Y aun así, ella no los maldijo.

Solo cerró los ojos y tembló.

Porque los hijos siempre quitan más de lo quedan.

Hubo un tiempo en que la llamaron Tonantzin,

y bailaban en su honor al amanecer.

Luego vinieron los hombres de cruz y hierro,

y la vistieron con otro nombre,

pero el eco de su canto siguió entre los cerros.

Ahora, cuando el viento baja entre los valles,

se oye su voz:

una voz antigua, dolida,

que promete agua al que sufre

y piedra al que olvida.

Porque la Madre no muere.

Solo espera.

Y cuando despierte del todo,

volverá a cubrir el mundo con verde y con silencio.

Laredo and its twin across the water lay half in dust, half in dream. On one shore, the banner of the Confederacy hung like a wound in the wind; on the other, the tricolor of Mexico wavered in the same heat. No man claimed the river between them, though both drank from it and cast their dead within its current. The streets were mire and hoofprint, lined with cantinas where traders, smugglers, confederates and mercenaries spoke in tongues of loss.

By night, the levee burned with lantern light, and from the water rose laughter, gunfire, and the low prayer of beasts; each sound a psalm to the same god of want. Between the two Laredos, the Río Bravo ran low and black, its surface broken by drifting cotton bales swollen with water. They moved downstream like corpses, pale and silent, and the smell of rot clung to the banks. The strong current bore south all things men sought to hold, and could not.

He stepped off the boat before it touched the dock, his boots sinking into mud that smelled of salt and smoke. He had ferried Confederates through this town before, many times, and the river had carried all their fortunes and failures alike. The smell of the cotton made him uneasy; it was always there, but today it seemed sharper, heavier.

A man came down the pier, riding the morning haze, and for a moment, he thought he recognized him. Maybe a Mexican officer or from the Union or maybe no one. He shrugged and moved on. There was always someone like that in these border towns: a shadow at the edge of things, who guided and vanished, leaving men to pay for what they thought was their own cunning.

News traveled slowly, but even here, men spoke in hushed voices of Appomattox; how General Lee had laid down his sword in Virginia, and the rebellion’s heart had finally broken. The word was that Union columns marched south now, closing on Brownsville to retake the last flickering holdouts on the border crossings. The gray coats in Laredo knew it, too; their cause undone, their future shrinking with every kilometer of blue advancing through the dust. Surrender hung in the air, heavy as the river mist, and every man sensed the world was shifting beneath his boots.

Everything was falling apart. The war had turned, and the men in gray were drifting with it; their destinies shaped by their hopeless ambition. Wreckage from recent skirmishes floated past: shards of wood, torn flags, and rusted sabres; a reminder of men who thought themselves immune to ruin. The Río Bravo carried the faint smell of iron and rot, of dreams gone sour. And somewhere, just at the edge of memory, there was that half-remembered presence; the one who had always been there, watching, turning men’s plans against themselves. Or perhaps it was only the fever talking. Either way, the river did not care, and neither did the world.

The Confederate officer appeared then, stumbling from the dock, clutching a satchel of gold that had no hope of saving him. His gray coat was torn, the brass dull beneath the dust, and the men behind him looked less like soldiers than ghosts still bound by habit. He looked through the river glare at the smuggler waiting by the flatboat with his crew, suspicion already hanging between them like heat. No words were needed; neither trusted the other, and yet the gold made liars of both.

The Río Bravo narrowed as the boat pushed down river, mud banks leaning close, reeds whispering against the hull. Empty crates and pallets drifted past, swollen, like corpses bobbing toward the sea. The Confederate officer leaned against a crate, sweating through his coat. Around him, six men shifted nervously, rifles across their laps. Each carried the same fevered hope: that the river, the smuggler , or some trick of luck might preserve what the war had left.

The smuggler eyed them all. He saw desperation dressed in worn gray, clutching gold that would bring nothing but death. These men, once proud at Palmito Ranch, thinking themselves the last wall against the inevitable; now moved as if the world had ended and left them behind. The officer’s gaze, hollow and restless, carried the memory of battles where hope was already a shadow. They lived in denial, clinging to stories and silence, not ready to hear how surrender had crossed the country like a slow wind. The war was finished, but in their faces, the smuggler saw men unready to bury its ghost.

The flat boat drifted loose first, and hours passed with little change after . The river bent sharp, hiding sandbars and snags beneath its ochre surface. Poles struck mud, then water, then wood, and the boat lurched forward a few meters before halting again. The current, weak here, whispered of patience, of inevitability, of all the men who had tried and failed to conquer it.

They worked through the night, torchlight flickering across the cotton bales, shadows moving like fever under the skin. Rats scuttled along the hull, unafraid. Somewhere far downriver , the marshes were thick with reeds and the promise of men waiting, hidden, watching.

The confederate posse huddled together, whispering, watching shadows. The smuggler thought he saw a figure at the edge of the reeds, unmoving, just beyond sight. He blinked ; gone. Only logs floated by, swollen and dark.

“You’ll need to keep your eyes on the river,” the smuggler said. “It tells you what walks here, and who’s already gone.”

The officers’s jaw tightened. He didn’t look away.

“I know these waters,” he said. “I’ve escaped worse. I’m not dying here.”

The smuggler watched him, silent. Puerto Bagdad drew men who believed themselves clever, certain they could outrun the current. But the war knew which way the tide had turned. It measured their pride, marked them for defeat, and held their names among those already lost for choosing the wrong side. The river carried every story, every scheme. Some things you didn’t say out loud; the desperation was in the air, and the water remembered all.

At night, the river swelled black and wide. Mist rolled off the water, curling like smoke from distant fires. By morning, the officer’s courage had gone dry. The marshes seemed to close in, reeds slapping the sides of the boat like fingers. The smuggler pushed the pole deeper, silently, always watching, always measuring. He knew the river, he knew the men, he knew the price that history always demanded.

He traveled with three fellow bandidos, friends in the river trade, men who trusted him to know the currents and keep them alive. Each carried a rifle, each carried greed, each carried fear. The bandidos and the Confederate soldiers eyed one another with suspicion, their alliances thin as river mist. Both camps were uneasy knowing that what bound them together was not loyalty, but the promise of gold. Greed twisted in the air between them, a fever neither side cared to admit, yet both suffered. In the hush before dawn, their hands hovered near weapons, their thoughts restless, each man wondering who might betray whom once the river’s secrets gave way to fortune.

A figure stood on the far bank: the Union Major, calm as a shadow at noon. He did not call out, only raised a small mirror that caught the sun and turned it toward them, a flicker of light that said more than words. Somewhere upriver, soldiers waited in the reeds and timber, guns laid across their knees, ready to close the river’s throat when the boat came through. He vanished behind the trees the moment the smuggler caught the flicker in his eyes ; as if he knew his signal had already been seen.

They drifted downriver in silence, listening to the occasional creak of the oars, the slap of reeds against the hull, the slow procession of cotton bales that drifted past like reminders of corpses. Insects and birds sang their lullabies under the rising sun, but the sound only sharpened the men’s nerves as the heat began to bite through their skin.

He thought of how the Major had drawn them into this. It had not been a request. He had cornered them weeks ago, at the edge of some nameless town in western Texas.

The job had gone wrong before it began. They’d moved the cargo upriver under cover of night, thinking themselves unseen. Medicine, gunpowder, weapons; tribute for Colonel Benavides, who still believed the river could keep the Confederacy alive a little longer. He’d fought off the Yankees once at Laredo and thought the river would serve him again. But pride runs shallow, and the Union had been waiting.

Men fell first; sharp cracks in the dark, rifles cutting through shadows, screams swallowed by the marsh. The smuggler watched from behind the reeds as one by one his companions were cut down, or dragged screaming into the trees. Some he had known for years. All dead before the river.

And then the Major appeared, walking slowly, deliberate, as if the night belonged to him. Union troops marching behind him, rifles ready, but he carried nothing. Just his blue hat in his hand, the calm of a man who knew the world bent to his presence.

“You thought the night would hide you,” the Major said, his voice flat and final, echoing among the wounded. “But the night keeps nothing. It watches and remembers. Men are measured by darkness as by daylight, and none leave its judgment behind.”

The smuggler tightened his grip on his rifle. His hands shook, but he did not speak.

“I could have you all executed. It would please the law, and the law is only the shadow cast by power. But men are not ends; they are means. There is one I seek, a name the Union wants claimed. Until he is in my grasp, you are useful, and use is the only reprieve left to men in the path of history. Between the edge of death and the weight of purpose, men are swept along, never knowing which side of the tide will bear them away. Your value is measured only by what the current demands.”

Mercy, the smuggler thought, was only the illusion of shelter before the storm..

“You will take the bounty,” the Major said, his head angling toward the marshes where blue coats waited, silent as fate. “Guide me well. The one I seek is running with what’s left of value in this war: gold, secrets, the last breath of a dying cause. Men like you … who profit in the churn, are not condemned by me. You are the gears that turn in the shadow of every empire, the hands that sift through ruin and carry the spoils forward. The tide respects those who endure and adapt; it has no quarrel with the clever or the hungry. You serve the current, as we all do, and for a while, that keeps you alive. Refuse, and you’ll hang. But even the gallows are only another crossing, another cog in the machinery that grinds men down. In the end, law is driftwood; meaningless to the current and to the men it sweeps away.”

The smuggler looked at his friends, the ones who had survived the initial shots, their faces pale, sweat running in dark streaks through dirt and blood. Some nodded, some whispered prayers, some looked as if they had already died.

The major’s eyes rested on him, unblinking, patient. “You have until I count ten. One… two…”

By the time he reached ten, the smuggler had made his choice. He would guide the confederate party to the ambush. He would survive, and the others… some would follow, some would not. The dead already spoke of the cost, and the living were learning it too.

He knew the Major’s calm had never been kindness. It was power, absolute and inexorable. The memory of that calm slid back into him now, not as a dream but as a map; one that had guided feet and horses into a place where men were picked apart.

That season the river ran lower than any man could remember. Men muttered the current had turned against them, obeying some will older than flags. The low water showed more bank than river, more mud than passage, and the road to Puerto Bagdad ran through that exposed marshland.

When the boat scraped bottom, the officer ordered them ashore. They took the cargo to horses and led the beasts into the marshes on foot, dragging bales and crates as the major had planned. The smuggler’s knowledge of the flats had been the price of his bargain; the Major had used it to steer them toward the shallow zone where hoof and boot would bog and breath would shorten. It was not a channel the Major wanted, but a choke; an expanse of reeds and sucking mud before Puerto Bagdad where men could be made easy targets.

They moved into the marsh with the sun bearing down, boots sinking in silt, horses straining under cotton and barrels. Mosquitoes rose like a living thing; the air sat heavy with rot. Each step toward the mesquite groves pulled them deeper into a hollow that swallowed sound. The second detachment, the gray coats meant to meet them, came late; trudging through the same muck, their uniforms dark with water. The low river had stalled both parties and handed them, in turn, to the place the Major had chosen.

Mesquites stood like dark teeth along the hollow, reeds tall enough to hide waiting men. When the second Confederate detachment finally emerged from the reeds, their faces were worn and suspicious; comrades looked like strangers. The smuggler felt the ambush settle on him then, not as surprise but as the slow closing of a trap he had helped set.

The officer dismounted, boots dull with mud, sabre at his side. “You’re late,” he said. His voice cut the thick air. “The others have been waiting since noon.”

No one answered. Only the river whispered behind the reeds, slow and patient, though even that sound seemed diminished, as if it too were holding its breath.

“You’ll find the bales lighter than promised,” the officer continued, tossing a coin that caught the dying sun. “War strips us lean. But gold is still gold. Provided you prove yourselves worth it.”

One of the smugglers spat into the mud. “Worth more than the rags you’re wearin’.”

Pistols shifted. The grove constricted around them. For a heartbeat, the insects went quiet. The men felt the weight of something waiting; not in the reeds, not in the marsh, but above them, unseen. The smuggler stepped forward, slow. “Gold’s gold,” he said. “But we don’t bleed for your flag.”

The officer smiled thinly. “No,” he said. “You bleed for whoever payin..”

The wind died. The river stilled. And in that silence, they felt it: the presence of the inevitable, watching, calculating, certain. The drought that should not have been, the stillness in the air, the way even the birds waited; all of it bent to a will that was not their own.

Above the hollow, a hawk turned wide circles over the marsh. Then it veered west, and the first barrel of a colt cracked.

A bugle sounded from the reeds, shrill and ragged, and the grove erupted. Muzzles flared, white smoke boiling up in the dusk. The first gray coat fell backward with his throat gone, boots drumming the mud. Horses screamed and tore at their reins.

The smugglers scattered, cursing, pistols drawn too late. From the tree line surged the Union men; blue coats low in the reeds, rifles lifted, firing with measured calm. It was no brawl, no skirmish. It was slaughter.

The Confederate officer’s sabre caught light once, bright as a flare. He shouted his men into line, but they folded fast, gray cloth ripping under the hail of lead. The smugglers were caught between, some crying for quarter, others firing wild at whoever moved.

And then he came.

The Major stepped from the smoke like he’d been born of it, hat shadowing his eyes, colt revolver steady in one hand, saber in the other. He did not shout, nor run, nor flinch. His voice carried low, almost kind, as he walked among the dying.

“There is no salvation in rebellion,” he said, driving the sabre into a Confederate’s chest and wrenching it free. “Nor in profit without providence.”

A smuggler, wounded and crawling, looked up at him with blood in his teeth. “We took your bargain,” he rasped. “We chose…”

The Major looked down, calm amid the noise.

“You chose nothing,” he said. “I only granted an extension to a sentence already written.”

Then he drove the blade through his spine.

The Union men advanced with bayonets, their faces set and pale. But their commander’s hand moved quicker, calmer, swifter … like a teacher correcting errors, precise in his brutality. He fired once into the officer’s horse, and the beast shrieked, collapsing, crushing its rider. The Confederate clawed in the mud, saber still in hand, but the Union officer stood over him, revolver aimed down.

“Aint’ no mistakin’ you.. “, the officer said softly , with recognition. ” you ordered fire at Sumter”

The confederate officer spat mud and blood. “Traitor.”

The Major’s gaze lingered.

“It was your vanity and greed that drew me here,” he said, his voice measured, almost contemplative. “The war is done, but men like you refuse its ending. You run with your pride and your gold, believing yourself outside the reckoning. Ranks, uniforms… these are only names men give themselves, badges of borrowed power. The tide knows nothing of such things. History is a tapestry, and loose ends must be seen to. The flow doesn’t care for the shape of victory, only for completion. I find a certain art in it… the last strokes, the final judgments; because in the details, time finds its meaning. In the end, it is not the uniform that matters, but the settling of accounts.”

The revolver barked, and the word was buried in the earth with him.

All around, men begged. The bandidos who’d thought themselves clever, gray coats who’d dreamed of escape, all broken in the reeds.

The Major moved through the bodies, calm and deliberate, the air thick with powder and rot. He gave no ear to their pleas. One by one he ended them, the smuggler remained, crouched low among the roots where the marsh met the shallows .

The gold lay scattered among them, bright even in the mud, a fool’s sun for dying men. His eyes fixed on it gleaming through the smoke , close enough to reach, close enough to die for.

Then the rain came. Slow at first, then harder, till the marsh began to swell. Bodies rose, turning, the blood-stained cotton and horses drifting back toward the river’s pull.

He looked once more at the gold, at the dying light across the water, and turned away. The river was rising. He slid into the reeds and let the mud take him, and when the Union men passed, he was gone.

The Major’s boots sank slow in the mud as he approached the place where the man had been. He holstered his pistol, wiped his blade on his coat. His eyes lingered on the current ; not searching, not surprised, only measuring… as if the escape too had been part of the design. He stood watching the current claim the field. The rain hammered his hat brim, his coat soaked through, and the men beside him were gathering what they could: rifle, packs, coins, their dead comrades. He raised his hand.

“Leave it”, he said. “It belongs to the river now.”

He stepped closer to the bank, his face lit by the pale shimmer of lightning over the now flooding marshes . The men behind him hesitated, their burdens heavy. The Major spoke again, his voice low, shaped by the rain and the hiss of the water.

“Let it take what it’s owed. It has fed on men before, and it will again. Gray or blue, saint or sinner … all the same once they’re in its mouth.”

He paused, as if listening for the river’s answer.

“See how it takes them,” he said. “It remembers no flags, no vows, no names. It drinks all the same blood and makes no distinction. The water bears them away and leaves no record.”

The smuggler crawled deeper into the roots, pistol empty, lungs burning. He could still hear the Major’s voice, steady and unhurried, carried by the wind along the water.

The mud clung to his boots, heavy as guilt. He did not look back. The river would remember enough for both of them.

He felt a sickness stir in him, not of the body but of the soul. The river had taken all, and it would take more. Men came and went, their colors washing into one another until no border remained between sin and salvation. The Confederates had paid, the smugglers before them had paid, and he… he would pay too.

Not freedom, not guilt, not even life itself. Only debt. A debt the river remembered, a debt the Major whispered to it with words soft as smoke and cold as blood.

He rose, moving through the marsh, mud heavy on his legs, lungs burning, senses sharpened to the slow, patient pulse of the water. Behind him, the river pulled the dead, the gold, the sins ; all of it back toward its mouth. And somewhere in that endless flow, he felt the major’s presence, not as man but as measure, counting and weighing what had been given, what had been taken.

Around him, the marsh began to hum with the rain, the slow movement of the current, the faint groans of the dying slowly fading behind him.

He moved through it all, silent, careful, feeling the weight of inevitability settle into his bones. He understood now that the Major had not spared him; he had marked him. Not for mercy, but for recognition. For survival at the price of everything else.

He did not stop. He would not stop. And the river, patient as always, would carry what it must, leaving him to the debt he now understood he owed ; not gold, not glory, not even life, but the simple knowledge that it had all been taken, and he had survived.

He reached Linares by the turn of the next moon, bones aching, skin scorched by wind and sun, each step heavier than the last. Nights had offered no rest, only whispers of the river in the reeds, the ghosts of men he had left behind pressed into his shadow. The road seemed endless, each hill and hollow folding time into itself, and with every kilometer he felt the weight of the blood, the gold, and the silence he carried alone. By the time the town rose before him, he was not the man who had left the marshes … only a shadow moving through a land that had learned to forget.

The road wound through dry hills, thorn and dust, where the wind moved like a whisper through the bones of cattle left to bleach. He had not spoken in days. The sky above him was wide and pale, a lid over a land long emptied of grace.

Linares lay quiet at dusk, the bells of its church tolling slow. The sound carried down the narrow streets, through the jacarandas shedding purple on the stones. A few lanterns burned in the windows, dim and yellow, and the smell of tortillas drifted faintly from some back kitchen. It might have been a holy town once.

He entered it like a ghost.

At the cantina by the plaza, men looked up and looked away again. He took a corner seat, ordered mezcal, and drank in silence. When he caught his reflection in the bottle’s neck, he did not know the man staring back ; eyes sunken, face marked by something deeper than fatigue.

He thought of the Major; that calm voice, that hand tracing the water, the way the river seemed to bend toward his words.

It struck him now that the he was no man of sides. Not Union nor Rebel, not law nor outlaw. He was older than any of it. He merely walked where blood had already chosen to fall.

And the smuggler, by surviving, had joined his trail.

He left the cantina and walked to the church. Its doors stood open. Inside, candles burned before la virgen , and a priest knelt at the altar, his whisper lost in the echo of stone. The smuggler watched a long while, then crossed himself without knowing why.

He knelt too, but no prayer came.

What rose in him instead was the sound of the river; the slow, endless current that bore everything downstream, washing away trails of any men.

He realized then that the Major’s lesson had not been of mercy, but of order. That in the great account of things, survival was only postponement, and every man was drawn, in time, to pay his due.

Outside, a wind passed through the plaza, rattling the jacarandas. Petals fell like bruised rain across the stones.

He left the church and did not look back. Somewhere beyond in the border; the river still moved, dark and certain.

By the spring of sixty-seven, the smuggler had taken another name and another cause.

He wore the brown coat of Juárez’s army now, the badge of the republic pinned over a chest that had once borne no flag but hunger. They said the Empire was dying in Querétaro, that Maximilian himself was caged in the city, pale as a saint, waiting for the firing line. But men were still dying for him in the dust, and the trail of blood had only changed course.

His company waited outside the city, their campfires dim against the dry hills. He sat by one, cleaning his rifle, when a familiar voice came through the smoke … low, calm, and merciless in its certainty.

“You keep good habits,” the voice said.

He looked up, and there he was. The Major. No older. No younger. Same pale eyes, same stillness in the way he held himself ; as if the world turned slower around him. His coat was Juárez’s blue now, but the badge could not disguise what he was.

“I thought you’d be up in Washington,” he said.

The Majors’s lips curved faintly. “Still chasing men, I see… under new banners.”

Around them, the wind carried the noise of artillery from the city, the hollow boom and echo of walls dying.

“I knew I would see you again ,” the smuggler said.

The Major ’s eyes narrowed, a slow shadow across his face. “It was always coming. The river, the roads, the wind itself … they do not forget. Nor do I.”

The smuggler said nothing, the weight of that truth settling like dust in the smoke-choked air.

The Major looked toward the lights of Querétaro, the sky above it pulsing faintly with fire. “Another empire ending,” he said. “They fall the same, you know. Flags change, tongues change, but the men beneath them are the same flesh. The same greed. The same death.”

He turned to the smuggler. “Tell me, do you still carry gold?”

The smuggler’s hand clenched. “No, ya no.”

The Major nodded. “Good. You have learned, then, what cannot be kept.”

He stepped closer, his shadow falling over the man’s face. “But remember this: the tide takes all, and returns all. Men may think they escape, but the flow never forgets.”

The smuggler felt the chill in his chest again; the same as that day by the marshes of the Río Bravo. He looked at the Major and knew that whatever battle waited in Querétaro would not end anything. Not for him. Not for the world.

The Major turned away, heading toward the fires where Juárez’s troops gathered. The men hailed him as “Coronel.”

The smuggler watched him go, the shape of him swallowed by dust and smoke. He knew the tide had found its way back into war and that he, once again, would follow its current until it claimed what was owed.

The church lay in ruins. Its roof had caved with the weight of seasons, and the wind that once carried bells now passed unhindered through the open vault. Its walls leaned like old men who had lost the strength to stand. Vines crawled through what had been the sacristy. The altar stone lay split in two, its fracture lined with dust. Zanates flew where incense once rose, cutting dark arcs through the roofless nave and nesting where the saints once stood.

The priest stood there, a man returned to the bones of his youth. He had grown up here, barefoot among the nopales, baptized at the same font where now scorpions nested. He had knelt here and watched candles gutter against the stone. He touched the wall, and the dust clung to his fingers. He pressed them to his lips, tasting earth, lime, ash. He walked across the nave where the tiles were broken, and weeds had grown between them.

A voice rose from the shadowed apse.

“You’ve come back.”

The priest turned. An old man sat on the broken step, bent and white-haired, his hands resting as if carved from the stone itself. His eyes caught the light faintly, pale, unhurried.

“This was my church,” the priest said, his voice tinged with nostalgia.

“It was never only yours. It was rock before it was raised, and it will be rock when the last name of it is forgotten,” said the old man.

The priest’s throat worked, but no words came.

“You see loss, but loss is only a name men give to the turning of things,” the old man said, shifting his wooden cane in his hands.

“And what about faith?” challenged the priest.

The old man looked at him with a calm that pressed like desert heat. “Faith is a season. You tend it and it blooms, and its people harvest its comfort, its songs. It was real while it was sung. Then it dries and the stalks rattle in the wind. Do you call the wind false because it scatters the husks?”

“Time moves,” he continued. “Nothing is hidden from it, but odes do not punish. You, I, the stones, the wind: these are witnesses, not executioners. And yet… even in the darkest hours, when there was nothing, something grew, somewhere.”

The priest lowered his gaze. He whispered, “But if all passes, what remains?”

“The turning itself. The stone becomes dust, the dust becomes soil, the soil feeds the root. Destruction is the other face of birth. You call it ruin, but I call it return,” replied the old man calmly.

“Do not mourn what ends. Even your grief will one day be gathered back. All is held in the big scheme of things; all is remembered.”

The priest’s throat tightened. “It does make me feel small.”

“Good. It is always right to feel the smallness. From it, you can see more, the stars, the mountains, the heat in your hands, the cool in the shade. You see what men call miracles, but it is only the passing of days, of seasons, of choice.”

The priest paused. “So… we are free.”

“Yes,” said the old man. “Free to stumble, to love, to fail, to rise. The wind does not ask; the river does not choose. And yet they carve valleys and bring rain. You, too, will leave your mark as they do.”

The priest felt the weight of years loosen; not with despair but with a strange calm, as if the ruins themselves enfolded him in their arms. His eyes searched for the old man. In the lines of his face, he saw not merely age but an order older than age itself, the weight of years uncounted. He thought of verses half-remembered, of time without end.

“Go on, father. Watch for a moment and wait. Your time is not gone; it has been given back,” the old man said with a smile. “And know that what ends is not lost.”

And in his voice the priest felt neither judgment nor mercy, but something vaster that held both a quiet that was not emptiness but fullness.

The priest sat on the stone, knees pressed to dust, and for a moment, when he closed his eyes, he was an altar boy again, heart quick, hands folded, listening for something that could not be spoken.

The zanates dipped and wheeled through the open rafters, their wings scattering light, and when the priest opened his eyes, he knew the church was not ruined but completed, its end no less sacred than its beginning.

The old man placed a hand on the priest’s shoulder light as a moth’s wing. “Remember, Father,” he said, “what ends is not lost.”

He nodded once, a gesture of farewell, and walked out through the nave, his cane echoing in the empty church. The priest listened to the sound until it faded into silence, and then there was only the wind and the birds, and the lingering scent of earth and candle wax.

They hadn’t much but they were happy. The girl helped her family work by taking care of the two goats and feeding the chickens each morning. Her father and brother worked long days in the fields of the hacienda, returning home with dust in their lungs and silence in their bones. At home, she and her mother prepared simple meals, mostly beans a little burnt at the bottom and rice so plain it tasted like nothing unless they had salt, stretching what little they had. Sometimes her stomach ached with hunger, but she found comfort in the murmurs of the wind and in the warmth of the sun that fell in golden sheets across the cornfields.

At dusk, she often sat beyond the edge of the sown land, watching the Sierra Madre sink into the horizon. Reddish and pink hues spilled across the sky like brushstrokes from God himself, and she wondered if heaven looked like that. Her mother told her they were God’s children, and that in times of hardship they must pray and endure. One day, she promised, they would all join him, where there was no hunger or pain, but only those with good hearts would be welcomed.

Every Sunday, the villagers gathered at the humble chapel. The priest traveled from a neighboring town to deliver the sermon, speaking of obedience, humility, and the promise of a better world beyond this one, so long as good remained in their hearts.

After Mass, the peons shared what little joy they could: food, music, dancing. But whispers of distant revolts filtered through the village like the desert wind. People were growing tired. Tired of hunger. Tired of injustice. Her brother once said the men in the hacienda slept in soft beds and never went without food, but they carried rifles and locked their gates. “That’s why nothing changes,” he said. “They keep what we need and leave us the crumbs.” Their mother hushed him, repeating the priest’s words. God would judge the good and the wicked alike.

As the girl grew, so did her beauty, and by fifteen she had become the quiet center of attention. Neighboring boys offered her tortillas just to see her smile. After Mass everyone greeted her with kind eyes and shy nods. Everyone but her mother. One day her mother warned her. “Go straight home from the store, do you hear? The men act nice, but don’t talk to them.” The girl didn’t understand, but she knew her mother’s hand was swift, so she stayed close to the animals instead. She found peace in the folds of the hills with the goats, where the wind spoke more honestly than most people.

One afternoon, walking home down the dusty road, she saw riders ahead: charros in dark embroidered jackets, carrying whips and rifles but no cattle. The one leading them wore faded brown and rode a black horse. Don Ezequiel. She recognized his eyes, not for their cruelty, but their strange sadness. He reined his horse and asked in a dry voice, “¿Quién es tu padre?” She answered, “Juan Buendía.” He nodded once. “Dale mis saludos.” They rode off, spurs jingling, and she stood there until the dust settled, a chill blooming under her ribs.

Days passed. Then one Sunday, as the family returned from Mass, the same men waited outside their humble adobe house. The air was heavy. The only sound was the slow breath of the horses. Don Ezequiel dismounted and walked toward them. Her father looked confused, her mother terrified. She seemed to have always known this moment would come.

“Buenas tardes, familia Buendía,” said Don Ezequiel. “I’ve come to take your daughter as my wife.”

The girl’s voice trembled. “Papá… what does that mean?”

Two of the men brought a saddled horse beside her.

“It means,” her father said, avoiding her eyes, “you’ll go to Don Ezequiel’s house. You’re getting married.”

Her mother and brother stood frozen. Their eyes burned with helpless fury, but the polished steel of the men’s revolvers kept them silent. With no more words, she was lifted onto the horse. She twisted in the saddle and looked back at her small home, at her brother’s face, but he stared at his huaraches on the dirt. Her family and her home looked smaller now, as if they were already forgetting her.

At the hacienda , they gave her a small room. The women washed her, dressed her, and combed her hair. She missed the goats, the smell they left on her hands, and her mother’s cooking. The softness of her new clothes felt strange, as if they belonged to someone else. In the kitchen, there were fruits and sweets, but no one spoke to her. The women looked at her with quiet pity. The men stayed near the stables. Don Ezequiel was distant, seen only in the mornings as he rode off.

The sunsets were lonelier now. From the narrow window of her room, she saw only a sliver of red sky. She missed the open plains and the whispers of the wind on her face.

Weeks passed, then came the wedding day.

The chapel was filled: charros, peasants, strangers she didn’t recognize. She was dressed in a simple white gown. A thin veil covered her face. The priest spoke of unity and divine blessing, but she understood little. When she looked for her mother, she found her standing in the back, weeping silently. No one came to speak to her. When Don Ezequiel pressed his lips to hers, she froze. Her mind raced: if this was God’s word, what became of those He didn’t speak for?

The reception was lavish. She sat beside him, silent. People congratulated Don Ezequiel. They smiled at her, but their smiles felt hollow. Her father drank with the charros until they had to take him away. Her brother danced with peasant girls, wearing brand-new charro clothes and a holster with a beautiful pistol. Neither looked her way.

She felt detached, as if watching someone else’s dream; one she couldn’t wake from. When he touched her hand, she didn’t flinch. When he pulled her close, she didn’t resist. And when the night ended, he led her to a larger room.

He reeked of aguardiente. He undressed her. She didn’t move.

He pushed her onto the bed and entered her. The pain was sharp. She cried out, then bit her lip, tasting blood. She called to God, but the room was silent.

The nights repeated. The pain dulled, and her silence grew.

She stared at the cracks, counting them, trying to remember the knot in the old kitchen table back home. Wondering if someone really cared at the dinner table or if they had already forgotten.

And so, time passed.

The girl began to forget how to pray.

Two winters passed. The earth dried and cracked like old skin, and so did she. The house groaned in the wind. Wood warped. Doors swelled. Shadows grew longer and never quite disappeared, even in the morning. She spoke little, only to the servants, and only when necessary. Don Ezequiel summoned her sometimes: to sit beside him at crowded parties or to his bed when the guests were gone. She never smiled; except the day he brought her two goats. She tried to hide it, but her mouth twitched anyway, just for a second; a gift not from him, but likely from her brother, who now rode with the charros and laughed as if he belonged with their leather clothes and metal pistols.

Her brother spoke to her sometimes, as if things were fine. She replied in monosyllables, her voice flat like dust settling on cold stone. He no longer complained about the suffering of others, now that his belly was full and he had a comfy bed. Sometimes she watched him, waiting for the old brother to come back, but he never did. She didn’t hate him, maybe she couldn’t, but whatever tied them together was gone, snapped like a dry twig, and sometimes she wondered if it had ever been real.

She tended to her goats. They were the only thing she could stand to touch. After one long argument that left her with a swollen lip and a black eye, she convinced Don Ezequiel to let her lead them out during sunset. She needed that hour; the open sky and the silence. It was the only time she felt alive.

Don Ezequiel would sometimes walk with her. He told stories of burned villages, of bandits turned into legends, of revolutions that never stayed won. Names she didn’t know. Places she would never see. He spoke of the world like a man who owned it, as if its tragedies were trophies. She listened, but what she heard was the absence: no stories of women, no tales of those who endured quietly. Only glories, betrayals, men who chose their deaths and were sung for it.

She began to wonder if she could disappear, if her name could slip into the dust without anyone noticing. If someone, somewhere, might sing her suffering into a corrido, or bury her with a whisper of her name.

Once, near the cornfields, she saw the charros hang a man from a mesquite ; a horse thief, they said. His eyes were swollen shut, mouth open to the flies. She stood there for a long time, staring at him swinging in the heat, and wondered if maybe that was kinder than another night beneath the cracked ceiling, with Don Ezequiel’s sweat pressing her down like a second skin.

The girl stopped going to church. Her mother had nothing left to say, only tears, and she had no use for tears. The goats, the hills, the dry wind: that was all she really had. She led them up toward the Sierra, where the land grew rough and the sky opened wider. The charros warned her: coyotes, bandits. But she didn’t care. She was not afraid of what could kill her, only of what kept her alive. She was watched from afar, but was left to herself.

The wind spoke in low, rattling voices. The same words, again and again. Something old. Something buried.

The hacienda grew quieter when she walked through. Servants looked down. Women stopped laughing. Men avoided her eyes. Her beauty was like a blade no one wanted to touch.

She was not a girl anymore. But a shadow that refused to vanish.

The fields were drier than usual, and at night, fires in the Sierra Madre glowed through the trees, carving a trail of red that was visible even from the plains. People prayed more than usual, uneasiness was in the air.

One dusk, when the sky burned pale orange and the light stretched thin over the Sierra, she found a man sitting next to a giant Yucca tree near the dry arroyo. He wasn’t there before. The goats hadn’t noticed him, neither had she. No horse, no dust trail or marks; He was just there.

His clothes, elegant, but travel worn. Not ragged but faded with time like a lithograph, the coat too long for the heat, boots too black for the desert dust, and a wide-brimmed black hat casting a shadow over his eyes. He seemed familiar, but his face was unreadable. Not old, but it projected an ageless presence. He looked back at her like he already knew her name. A soft smile plays on his lips. He bows his head slightly, as if greeting royalty.

“You’ve walked this trail many times”, he said, his voice rough, like stones tumbling in a stream. “But today you stopped.”

She didn’t answer. She kept her distance. The goats wandered ahead, unbothered by his presence.

“Your silence has weight to it, señorita. Like a church with no choir or a fiesta without mariachi. Heavy with what’s missing. “

“I wonder”, he said, watching the sky, “if you ever thought of going beyond the ridge. Just not looking back.”

She narrowed her eyes. “Who are you? I don’t know you.”

He smiled, but it was the kind that held no warmth. “A passerby. A listener. I follow the noise people leave when they try to be silent. “

She felt something tighten in her chest. Not fear, but something else.

“But I know you. And I’ve seen women in cages smile wider than you.”

He stood slowly, dusted off his coat, and stepped towards the goats. One of them walked to him, unafraid. He knelt and stroked its back with some kind of reverence.

“There were and are many like you”, he continued. “Buried alive. Waiting for the wind to carry them off.”

The girl didn’t reply. She closed her hands into fists.

He looked at her again, and this times his eyes were deep like a well you couldn’t see the bottom of. Not cruel but neither compassionate.

“But the wind doesn’t carry” he said. “It scatters, transforming seeds into new life and dust into distant memories, for better or for worse. “

She looked at the goats. The wind stills. The bird and insects have gone quiet.

“If you seek the road, you are far from it,” she says.

“Not all roads are drawn in form and dust. Some are carved in memory. In scars.”

They spoke about the land, the weather, the silence between the rains. His voice was calm, the way old riverbeds are dry, but holding the memory of ancient floods.

Each word he said carried its own weight, as if it had been rolled in the mouth and tested before being set free. He told her of roads and cities that slipped away into nothing, of paths that existed for only those willing to walk without looking back. He said that some chains were made of iron and other of promises, and both could be broken if one’s hand was steady enough.

The girl listened, thought her eyes stayed on the hills. She felt his words like the smell of smoke before the fire comes into view; something dangerous, something near.

“You’ve been counting your days here,” he said, thought it was not a question. “And I reckon you’ve decided they’re too many.”

The words settled in her chest like a stone dropped into a deep well.

He did not tell her what to do. Instead, he spoke of women who had walked away in the dark, leaving behind palaces and men and names that were never truly theirs. Of nights when the only sound was the crack of a match, and mornings when the sun rose over the ruins no one mourned. He made no promised of safety or happiness, only of change.

Then, just like that, he walked past her downhill, towards the darkening horizon that had once looked like heaven.

She didn’t look until he was gone. That night, she dreamed of fire. Not in horror, but in relief.

The dream followed her for weeks. She thought it would fade, but it seemed instead to be preparing itself; like something waiting for its moment to come.

That year’s fall came dry and windless. The fields cracked open like old skin, and the goats wandered farther to what a little they could find. Don Esequiel spoke often of new times; how the revolution had cleansed the land of vermin and heft in the hands of men who knew how to keep it. He said it like a prayer, or a warning. There was to be a gathering at the hacienda, a night to celebrate his position with the party men from the capital.

The banners hung heavy over the hacienda’s gates, red, green and white, each marked with the eagle and the serpent. Beyond, the courtyard swelled with voices; men in clean suits, polished boots, the smell of cigar smoke and roasted goat drifting with the brass music. Don Ezequiel moved among them like a crowned bull, his laughter louder than the trumpets. This was his night, his reward for backing the right party just before the shooting stopped, and he wore it like a crown.

She stood at his side for the first hours, a hand resting lightly on his arm when he introduced her. The dress he’d chosen for her shined under the oil lamps, gold threads catching the light. She was a symbol of his success, a beauty plucked from the dust and given to him by force and fate; it hardly mattered which.

It was then she saw him.

He was near the steps of the balcony, speaking with two men in gray uniforms. He wore the same coat, but now it looked brand new, and his hair was oiled, his boots shined. In the yellow light he could have passed for a government envoy, and the officials listened to his words and laughed at his jokes. But his eyes, cool and steady, found her across the crowd.

Later, when Ezequiel was swallowed by a knot of political allies, she moved towards the fountain, to gasp at least a small moment of air. He was already there, hands resting on the marble edges as though he had been expecting her.

“Do you know,” he said, not bothering with a greeting, “these men have been at war and revel both, a tide running back and forth. They speak of causes, but their only contest is for the largest chair. The good ones, the ones who came with hope in their fists, they’re in the ground now or else they’ve learned the taste of power and found it sweet, and they’re lost same as the rest.”

Burst of laughter spilled into the night. He straightened, his voice low enough to be heard only by her. “Watch them closely tonight. Listen to what they do not say. The walls and bars are not as solid as they seem.”

Then he was gone, swept into the smoke and music, trading words with the other capital men as thought they had always known him.

She stayed by the fountain longer than she meant to, watching him vanish into the crowd of sombreros and uniforms. The music swelled again, and the night pressed close, smelling of mezcal and sweat.

When she returned to the crowd, it was as the air had shifted slowly. She began to hear what had always been there: low voices in the party’s shadow corners, the quick, malicious glances from one man to another. Near the veranda, two colonels argued in murmurs over the division of some valley she’d never heard of. On the terrace, a merchant with golden rings on every finger smiled too widely as he promised his support in exchange for a rail contract.

Everywhere she turned, words concealed blades forged in greed.

Ezequiel, swollen with drinks and praise, clapped backs and made boasts about the land he’d acquired during these harsh days; how his loyalty had “helped share the nation’s future.” They laughed with him, but she was able to notice the way some of the guests’ smiles vanished as soon as he turned away. Another’s eyes followed the path of the stranger as he crossed the floor, speaking briefly to the governor’s aide, then slipping away to someone else’s ear.

By the time the music shifted to a slower waltz, she felt as thought the entire hacienda were a stage, and every player was rehearsing their betrayals for a later act.

She caught site of him once more, at the edge of the dance floor, dancing with a beautiful, sophisticated lady she didn’t saw before. He met her gaze briefly, then looked to the ceiling wooden beams as if drawing her attention to the weight above them.

That was when she understood: this night was not a celebration of sorts. It was a balance, and all it would take was one shift in its weight for it to come down.

She found her father near the card tables, a cigar smouldering between his fingers, his laughter louder than the others. Her brother stood at his side, already with the hard, narrow smile of men like Ezequiel who think that world is for them to take. They were talking and laughing with an officer whose medals caught the light like coins.

She passed them without saying a word. Their voices seemed as a port of the same foundation that kept the walls upright, same as the charros who appeared at her house years before. The same foundation he hinted was cracking from within.

The music shifted again, brighter now, and the crowd parted just enough for her to see him. He was on the dance floor, his frame cutting sharp line against the sophisticated woman who was wearing a dress in black satin. She was beautiful in a way that made the air colder; her dark eyes held no warmth, and her smile never reached them. Around her neck, a single silver chain caught the light.

They danced with precision, the band playing as thought they alone dictated the rhythm of the room. For an instant, she thought she saw the outline for something else; not two dancers, but a man and the shadow that followed every living thing.

When the song ended, he bowed to his partner, kissed her hand, and turned towards the balcony. He found her in the crowd without searching. He tilted his head as thought inviting her to follow him and so she did.

Outside, the air drove a cooler breeze, the sounds softened by distance. Lanterns swayed on the nights winds, casting shifting shapes across the stone.

“Some think their place will stand forever”, he said in a serious tone. “But everything they build is funded on debts the earth has not forgotten.” His gaze flicked towards the inside, where her father and brother still laughed and drank at the card table. “Every root must be cut for the tree to fall.”

Her heart beat quickened. She wanted to speak, but the words would not form.

She could see in the faint light his smile, which was almost kind. “When the music stops, you will know.”

He stepped away, rejoining the black-satin lady, and both disappeared into the dancing crowd.

The music swelled again the part, louder now, and she lipped back through the doors. He was already on the floor with the woman in black. They danced like a tide, slow and inevitable, their steps guiding the room and the dancers around them.

She felt the air in the hall grew warmer. She noticed a lantern, slightly ajar from its hook near the flags, its flame licking dangerously close to the fabric. Her eyes met his over the lady’s shoulder. He smiled and gave a small nod.

She crossed the room without a hurry, as thought going for a glass of wine. At the base of the lantern, she reached up to steady it; but tipped it instead. The flame caught one of the flag’s edges in a whisper.

For an instant, nothing happened. Then the green fabric transformed into orange, the fire climbing upward with a hunger that founds its own rhythm.

The first shouts came from the far ends of the room. She moved towards the main doors, but instead of opening them, she swung the iron bar down across the latches and slid the bolt in place. Guests pushed the heavy wooden panels, unaware it was sealed from within.

His voice vibrated in her mind like an echo: Every root must be cut.

Don Ezequiel stood by the main table, shouting for calm. The charros drew their pistols, trying to herd the crowd away from the flames. One woman tripped and fell; a soldier who tried to help her was shot in confusion. So, the officers pulled out their guns too. Shots rang out, and the screams drowned the music beneath them.

Smoke thickened, stinging her eyes. She ducked into the side hallway, towards the storage rooms. There, the oil barrels waited. She cracked one open, letting the sharp scent bloom, and dragged it across the floor towards the read doors; the other exit the guest might reach. She poured oil in a wide arc, then kicked a lantern from its hook. Fire leapt up like a beast.

By the time she returned to the main hall, the crowd had realized the doors would not open. Panic tore through them. He and the lady in black still danced, stepping over the dead and the screaming alike.

She saw her brother’s face appear in the smoke; red, twisted, coughing and scared. He looked like the boy he once was, but before she could do anything a falling beam crushed him. She had no time to look away.

Don Ezequiel, stumbled towards her from the smoke, his fine charro suit scorched, his face a mask of sweat and ash. In his hand, a silver revolver hung limp, the cylinder empty. His eyes were wild, not from bravery or rage but from the creeping certainty of doom.

“Ayúdame por favor!” he rasped, catching her by the wrist.

She could have pulled him toward the side corridor that let to the stables; the scape route she planned for herself. Instead, she guided him toward the main hall, where the smoke thickened and the cries sharpened into panic.

A burning rafter cracked and fell, cutting off their path. Ezequiel coughed, staggered, and dropped to one knee. On the far side of the room, through the chaos, she saw him and the lady. They stood holding each other, watching the mayhem bloom. Their smiles reminded her of the way she used to look at sunsets on the hills; amazed, in peace, and something close to happiness.

Ezequiel gasped for breath, reaching for her again. She bent low as if to help, but her hands found not his harm, but the strap of the chandelier’s winch. A par tug, and the iron mass groaned above them.

He saw her movement a moment too late. The great wheel of iron and glass crashed down, breaking him under its weight. His cry was short, swallowed by the roar of the fire.

She didn’t run. She walked through the chaos, past the stranger, who stepped aside for her as if she were the honoured guest of the night.

When she finally stepped into the open air, the locked doors behind her thundered with fists and boots, until all the sounds of the screams were swallowed by the flames. The night air burned her lungs as she walked away.

The dawn came in slow, a light pushing over the blackened ruins of the hacienda. Ash still drifted in the air, soft. Where the courtyard had been, there were only bodies; faces frozen in the last shapes their fear had given them. They carried no bodies out. There was no one left to carry them. The air inside still trembled with heat, and in the courtyard, the fountain had boiled away, leaving only a ring of ash and glass.

She sat on the low wall, her dress grey with soot. No one spoke to her; there was no one to speak. Far away, the church bell rang for the dead, though no priest had come.

He was gone. No sign of his boots on the dirt, no smell of his cologne, only the faint echo of laughter from somewhere far oof. They said the woman he danced with had hair black as a cuervo’s wing, and her eyes did not blink when the fire rose. No one knew her name.

She stayed there until the sun rose high, until the smell began to fade and the flies and zopilotes came. Then she stood, turned her back to the ruins, and began walking towards the hills.

Years had peeled away like the paint from the doors of old churches. Towns had risen and others fallen. Flags had changed their colours, their owners. The governor’s ballroom was filled with the clink of champagne cups and the dry murmurs of men whose fortunes had outlived their enemies. She stood near the back, her hair straked with white now, the dress black thought it was not a day of mourning. She didn’t come here to be seen. Yet the eyes that mattered found her. She had learned how to smile without speaking, how to stand still until the moment mattered.

Through the crowd, he came. No older than before, as if time had never touched him. Not a single line on his face. Not a grey hair. His suit looked European made. Hist subtle smile, unchanged.

“I was told you’d forgotten me.” He spoke. “I tried” she replied. “You have done well. The city knows your name. Both the dead and the living.” He looked at her while fixing his black hair. “The dead more than the leaving.” She replied giving him a dry smile.

He glanced at the men talking at the high small tables, politicians, generals, the new breed of landowners and industry barons. One raised a glass towards her.

“You have learned,” he said,” that the earth eats the living before it forgets the dead.”

She studied him, as if expecting the years to revel his trick. “You’re here for them”, she said.

“I’m here for everyone and for no one,” he replied, his eyes drifting over the room.

“And what will it cost?,” she asked, as if he might reveal the truth of the world.

He took a glass of champagne from a passing waiter. “It costs what it always costs.”

She sipped her wine, bitter and warm. “You took much from me that night.”

“You had much to give”

“And the price?” she pressed.

He tilted his head, as if weighing something invisible.

“The price is always the same, niña. It was the rest of your life. You’ve paid it, moneda por moneda, without knowing the sum.”

Her gaze drifted to the tall woman who approached. She was wearing a gown in the color of dried roses, gliding with a dancer’s grace. Her gaze deep and hollow as the space between church bells at night. She took his arm, and she recognized her from her black hair.

“And her?” She wondered.

He smiled faintly, the woman on his arm. “She does not speak of debts. Only collects them”

“Do you still follow me? She asked.

“I follow no one,” he said. “But I have always been where the roads end.”

“And mine?”

You have not yet reached it,” he said, and the black-haired woman spoke for the first time, her voice sweet and dry. “But the map is smaller now.”

They stood there in the center of many conversations, the sound of politics and power drifting like a distant sea. His eyes held the same quiet that had burned the night she left the hacienda in ashes.

“When the fire came,” he said, “you chose to open the door for it.”

“You lit the match.”

He shook his head slowly. “I only showed the darkness. You decided what do with the light.” He glanced towards the governor and the men he laughed with. “Men here and elsewhere have made the same choice, only they burn the land before the fire burns them.”

And then he was gone, the woman in dried roses with him, the air behind them carrying the faintest scent of smoke ; the kind that stays in your clothes long after the fire is out.

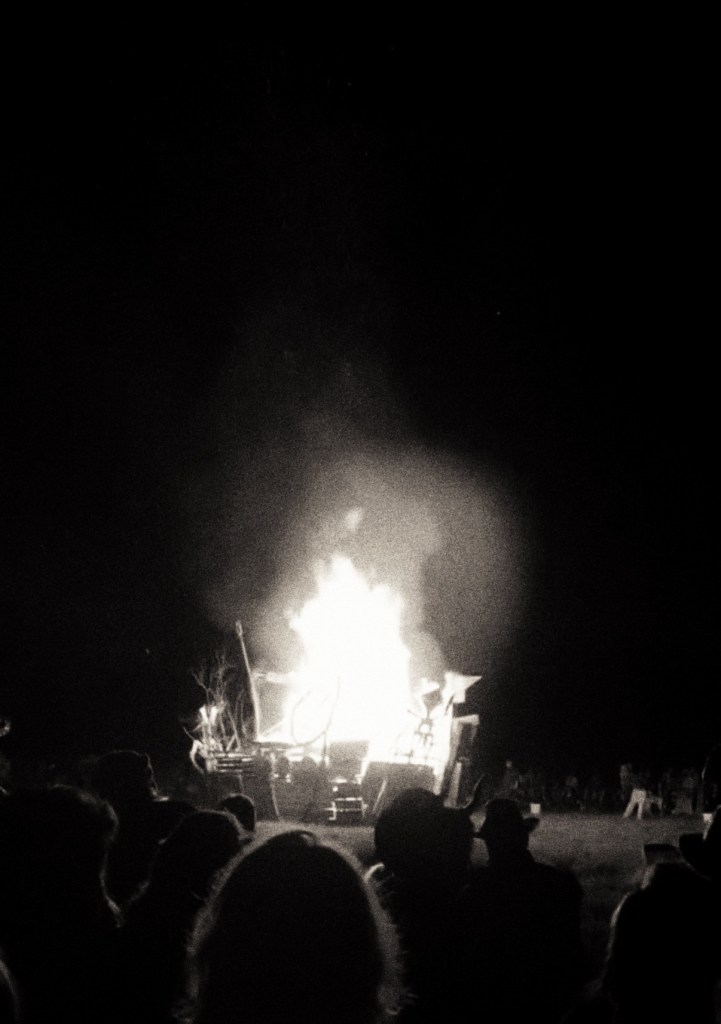

It was a cool summer night deep in the forest of Alversjö. Under the gaze of the green trees, we gathered, hundreds of souls drawn together by an unspoken longing. For a week, we had savored the sweet taste of freedom, leaving behind the confines of ordinary life like old clothes. Here, those yearning for connection found gentle hands reaching through the crowd, and those weary of the world’s boxes let their true selves dance wild beneath midnight’s starry mantle.

Warmth, acceptance, and love flowed among us like a refreshing current, wrapping each heart in its tender embrace. Each smile, each whispered compliment, became a spark, an infectious glow that wove us closer together, until we moved as one breathless tapestry of belonging. The magic of the night was not in the stars above, but in the constellation of spirits shining all around us, which exploded with happiness and joy to each drop of the beat in the dawn dancefloor of Mumima.

As the celebration reached its grand finale, we gathered reverently around the wooden idol, our bodies humming with anticipation as the rhythmic pulse of drums filled the air each beat a heartbeat echoing through the forest’s timeless presence. It felt as though the spirits of the past stirred among the trees, whispering their joy to us beneath the radiant flames.

When fire at last claimed the idol, the flames leaped toward the night sky, painting our faces with flickering warmth and light. In that glow, a shift swept strongly through the crowd: pure and primal, a surrender to ritual and renewal. Many, casting aside their garments, let the cool air and firelight caress their skin as they danced in an ecstatic circle around it, hearts opened wide to the promise of transformation and the sheer delight of being alive.

My friends and I watched the moment unfold, reflecting on our role, boundaries, and sense of belonging in this world. That night, the fire deepened our connections; new and old friendships grew stronger as we danced until sunrise. As I returned to camp at dawn, I realized something inside me had awakened, giving me new direction. I wasn’t reborn, but the fire reignited a forgotten part of my soul.

“I am perfectly aware that she was beautiful on the outside, but a dark and haunted forest on the inside. However, the mixture between her undeniable beauty and emotional intensity has left her image burnt into my soul.”

In life, there are moments that, for one reason or another, etch themselves into our memories with vivid details; these moments stand in stark contrast to the mundane and routine aspects of life. These moments usually carry significance to the persons who we have become today and if you stop to think for a second, some of them will easily resurface; a wedding, college graduation, your first kiss, and so on. Sometimes, in between this meticulously curated list created by our minds, there often lie odd instances, seemingly out of place, that cannot really fit directly into any of the symbolic categories of events. Nevertheless, we seem to remember these oddities with vivid details, usually at similarly off moments of our days. They are like those filler episodes of your favorite series that you don’t particularly like, or they don’t give any particularly any value to the story, but they leave an impression that keeps you wondering : Like that fly episode of Breaking Bad.

And so, this peculiar day comes back to me at the most unexpected times and momentarily fills me with uneasiness, flooding my mind with questions and then goes aways as swiftly as it arrived like a random leg cramp that painfully trembles all the way to your head with discomfort before vanishing as you shift position.

It was my fourth day in Stockholm after I moved away from my home country to pursue my post graduate degree. I have just picked up the keys to my new accommodation from the student housing department after I crashed a friend’s place for the first few days. Excited to start my new chapter in life in Sweden , I grabbed my 40-kilo life packed into two bags and took the metro. My new place was located close to the medborgarplatsen station in this building called Skrapan, a 1960’s tower that once housed the tax office then turned into student housing. The neighborhood was known for the many pubs, restaurants, and cafes where all the city hipsters use to hang out, which was quite cooler than the student enclaves outside the center where the international students usually were assigned to.

So, I enter my room which was located on the 4th floor, of a reasonable size for a bachelor. Mostly unfurnished with a small bed, a small kitchen, an unreasonable big toilet and nice balconet overlooking Götgatan, the street in which everything was happening on the neighborhood.

I planned to have some drinks with an old friend, and he told me that he will be on the neighborhood in 2 hours or so and since I didn’t have much to do and didn’t feel like unpacking, I wanted to sit somewhere outside to kill some time. From my window I spotted a small square adorned with some flowers and a little sculpture on its center, and I thought I could sit there and watch the people pass by and maybe take a walk if the mood hit me.

I went outside and sat on this concrete semicircle around the square looking at the people on the street, watching them going on with their lives – the weather, neither warm nor cold, marked the end of the summer giving way to the fall with its greyish sky, contrasting to the extremely warm August days back home. I haven’t really come to realize the big change in my life that was happening until I looked around and realize how different things really were from home, triggering a cascade of emotions that overwhelmed me for a moment. But still my moods were up and I found myself smiling there like an idiot for quite a while. I felt I sat there forever, yet just a few minutes have slipped by, my sense of time wasn’t fully adjusted yet with the jetlag, like a loading screen on a videogame caught in a loop with some animations as the new level or cut scene loads.

As I set there, lost in my thoughts, a middle-aged women entered the small square pulling a purple shopping cart bag with a small white dog, maybe a crossed French poodle. She walked up the small statue and she started mumbling some words that I couldn’t really comprehend; my Swedish was nonexistent at that point in time. She didn’t look particularly odd, her clothes were quite clean, color matched, and her hair was carefully groomed. She continued mumbling next to the small statue, which was a small cubist man-silhouette; like if she was worshipping an unknown urban deity. There were other people on the small square, but none seem to notice the small ritual of the woman; everybody kept into their own business.

I tried not cross glances with her and interrupt her with her little ritual, but I was quite curious trying to understand her mumbling words until she eventually noticed my presence. She ceased her mumbling as our eyes crossed paths , offering a smile that carried neither warmth nor coldness. She then turned facing me completely and approach with a few steps, which I have to say it made me anxious a little, maybe even embarrassed for interrupting a moment that felt quite personal. A part of me felt like just standing up and escaping the encounter, but the itch of curiosity kept me from moving.

As the woman moved toward me, she mumbled a phrase I didn’t understand and I replied – Sorry, I don’t speak Swedish- The woman stop for a second and it seems that she went into her memory to recall the translation – Death is just a door that we are afraid to open, but it always unlocked-.

Her words made my skin bristle as I felt a mix of fear and confusion, which made it clear that she was probably on the crazy side, so I was ready to stand up and scape a second after and as I was about to move , the woman turned around and went back to the statue to continue into her mumbling completely ignoring the reaction she left on my face, which made everything even more disturbing. I contained my haste to flee and kept my cool for a secondl, but before I could have a moment to think on the whole situation, the woman collapsed into the square ground making a big sound as her head hit the cobblestone and blood slowly started running through the gaps.

Stunned, it took me a moment to process the scene before me. As I sit there, a girl sitting on the other side of the square rushed to help her, which eventually I did as well. A strong smell of whiskey mixed with perfume overwhelmed us as we tried hold her head. Someone called the ambulance and eventually some waitress from a nearby restaurant came to help with some towels to stanch the bleeding. The woman kept mumbling nonstop , but it seems nobody really was listening to her words. Her dog stare at the whole thing silent and motionless; I completely forgot about it until we made room for the paramedics when they arrived.

I clearly remember the change of expression of one of the paramedics as they were pulling her into the ambulance while she kept mumbling to them. It was a big expression of confusion and a mix of fear. As they pulled her into the ambulance the paramedic told me if I could wait with the dog for a while until the police could come and pick it up, which I agreed since I still had to kill some time and quite frankly, I was still shocked of the whole thing.

The crowd dispersed and the ambulance vanished into the distance, and I found myself standing in the square with the small white dog by my side in front of the small pool of blood. Before the girl that help her with me left as well, I approached her and asked what the woman was mumbling to which she said – It was something about a gate being open and trying to walk through it, but it didn’t make sense at all. – and she walked away. As the police arrived to collect the dog, I was left bewildered by the whole thing, after that I just went on with my day trying to leave all behinf.

That day faded and life carried me forward as my went on with my studies and adjusting to my new life in Sweden. Months later, as the summer was started to kick in, I found myself having drinks with some friends at a bar . A good-looking brunette at the bar caught my attention, so I decided to make a move. As I approached her, her eyes stuck me with recognition – she was the paramedic of back then! My memories of that day came back as fast as when the water runs when you turn the tap and a feeling of uneasiness ran through my spine, but I remembered quite well about her expression after the woman spoke to her, so I was still curious about what she said to her that day.

I offered to ger her a drink and asked her if the remembered that day, and her smile changed to an expression of confusion, so I knew she did. We had a small chat and she told me that the woman died later at the hospital after a heart attack, but the doctors weren’t sure if it was related to that fall she had on the square, which made everything odder. I asked her if she could recall what the woman said when they were pulling her away – I remembered it very clearly. She said that she had opened the gate for a while and today she was going to walk through it because she was too curious – A grimly sensation passed through me as I listened to her words leaving a bunch of questions to what really happened that day. We changed our conversation into other things, leaving that unsettling day behind.

I still can’t find any answer or explanation to what went about, often wondering if it was all a just a creepy coincidence or something beyond our natural understanding of things, but I try not to think a about it, but now and then the woman’s words hunt me; making me question my sense of logic and ponder if life holds mysteries beyond our understanding.

Stående figur by Rune Rydelius.

Stuttgart , November 2013

We weren’t the best coders neither the best at managing a website, but for a time everybody was able to enter write something and collaborate in our endless-senseless writing. It was an annoying twitter for letting go our creativity and improve our writing skills. Somehow, it became a place to relieve secrets, tell amazing short stories, and let our feelings pour out.

One day the serves we had went down and most of the data was lost and many amazing short fragments coming from the hearts of random strangers with them. Bringing back the data was expensive and the book we planned wasn’t very successful. Eventually, we gave up and the server flashes a forbidden error.

I still refresh it sometimes, hoping that it will work out even though I was the owner of the server and I imagine some people still refresh it up to today and that we all connected with a single click and the little disappointing that it produces.

Monterrey, March 2010

Home gatherings became the preferred option, and staying home to play video games grew more appealing regardless of the favorable weather conditions. We discussed these activities more frequently than ever before, and the numerous stories we shared seemed more akin to horror fiction than reality. However, they were indeed true, as evidenced by the videos available online.

Walking the streets at night or hearing sirens while playing baseball brought feelings of powerlessness and mild sadness, but life continued. The constant news and social media rumors left us numb rather than surprised.

Every morning, heavy police presence in the neighborhood didn’t bring safety, just an expectation of something happening. Worry would pass quickly as we moved on with our lives. A classmate once said, “If it comes, we will just follow,” reflecting our shared understanding.

Near my apartment was a house with high walls and bodyguards. Rumors said it belonged to either a prosecutor or a big player in the game. Passing by daily, I wondered if they felt the same fear or even more danger. One day, all the bodyguards were gone, and the empty house had a large cloth at the entrance with text:

If you die today, would that person know that you love her?

Don’t wait. Tell her today

Despite everything, there remained a chance for love to blossom. When the piece of cloth was finally removed hours later, I couldn’t help but wonder if he had truly told her. We must embrace reality and adapt to its uncertainties, holding tight to each other and moving forward with hearts full of hope. Because hope is the only thing we had those days, that things could change for the better one day.

Narcopoetry – Monterrey 2010

As time passed, the police presence and bodyguards vacated the large residence, leaving me speculating about the outcome of the potentially tragic incident that occurred. Eventually, it became a distant memory, much like the countless sad narratives surrounding the ongoing war on drugs. From the folds of the Sierra Madre and to the riverbanks of the Rio Bravo, has been perennially marred by violence stemming from human ambition.

In the small northern towns, blood has always been shed – Los Cadetes de Linares